The value of hard work is one I’ve held for a long time. So when someone as smart as Naval Ravikant challenges the notion of hard work, I listened.

What does Naval get right about hard work? And what does he miss? Below I synthesize Naval’s riff on hard work with my experience of it in the real world, in the context of a career.

Who has listened to the @naval podcast on The Truth about Hard Work? I’ve been thinking about it today and wanna hear some perspectives. https://t.co/Ycd5nUaMkd

— stevanpopo (@StevanPopo) January 28, 2019

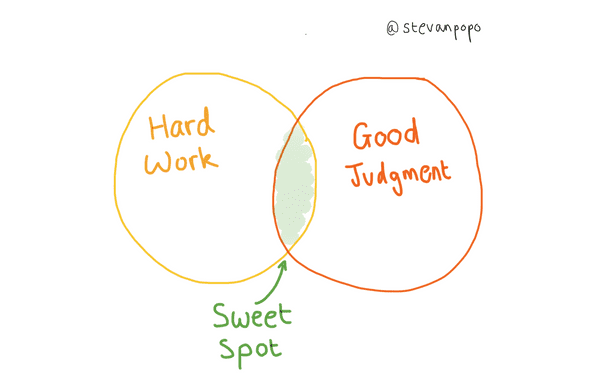

Hard Work vs. Judgement

"Because of the tools we have available, our judgment matters more than hard work."

I think there is some truth in this. We live in a high-leverage world. Tools (namely, the Internet and software) can make an individual’s actions many degrees more impactful.

Therefore, decision-making becomes more valuable. Choosing what to work on is increasingly important. As a thought experiment, think back to hunter-gatherer times. On a given day, a person’s simplified choice would be to hunt, gather or relax. In two scenario’s they get food and in one they don’t. But the difference between the two success scenarios is minimal (meat or berries). Today’s simplified choice might be: work for a breakout tech startup, work at a factory or relax. In two scenarios, you earn a wage and in one, you don’t. But note the difference in the work outcomes has the potential to be vastly different.

In a world where outcomes are so diverse, judgment matters more.

Hard Work vs Judgement

But I wouldn’t write hard work off yet. Working hard does not preclude having good judgment. And whilst I agree that having good judgment has become more important, I would still think that more hard work given the same level of judgment is at least equal, if not preferable.

Hard work vs. judgement is a false choice. Just as working hard vs. working smart is often positioned as a false choice. I’d argue its best to do both.

Busy Work

"But many people work hard for hard works sake."

Also true. General business is very pervasive in most workplaces, where the goal is less the work itself but equal parts giving the appearance of work. Clearly, this type of ‘busy work’ is less effective than actual work. It is particularly harmful if busy work comes at the expense of real work; say if an employee ‘works’ late and is therefore too tired to work effectively the next morning.

In aggregate, this type of ‘busy work’ is likely a bad thing, generating less impactful output for a team.

The Perception of Hard Work

But, for an individual, you could argue the merit of ‘busy work’ depending on the workplace. If a manager values hard work itself, then it follows that their employees would want to give the perception of hard work. This often leads to the ‘busy work’ described above.

Oftentimes, there is an implied pressure in effect. If all other members of a team are engaging in ‘busy work’, then to opt out is more significant.

Busy work is also linked to opportunity. If your manager values hard work and they are also in charge of promotions, then it follows that given two otherwise equal candidates, the one who displays more hard work is more likely to be promoted1.

In an idealized world, ‘busy work’ would be at zero and only real work would be valued. But in reality, producing the perception of hard work itself can be valuable and is missing from Naval’s argument.

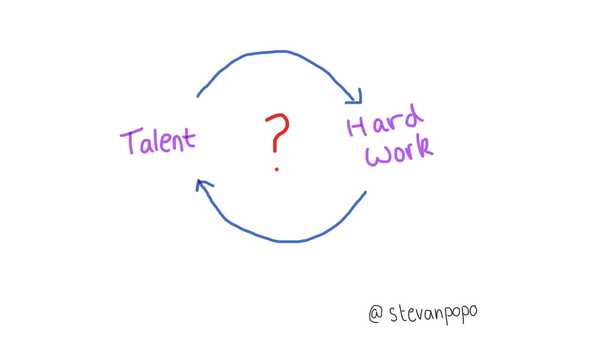

Hard Work vs. Talent

"Given the era that we live in, talent matters so much more than hard work."

This claim is most interesting for its use of the loaded word talent.

What does Naval mean by talent? Is talent an innate skill that someone is born with? Or is it something you’ve worked at to build said skill?

Depending on where you sit along this talent definition spectrum will surely decide how you qualify the above statement.

I’ll choose to skip the whole nature vs. nurture discussion of talent but offer one quick lens on this statement.

Hard Work and Deliberate Practice

A popular idea in the context of building skill, and therefore central to the talent debate, and tangentially to this hard work riff, is deliberate practice. Coined by researcher Anders Ericsson2, deliberate practice is a specific type of effortful practice that allows an individual to develop expertise.

It was also used by Cal Newport in his book So Good They Can’t Ignore You as the main tactic by which to build a good career.

One of the main findings of Ericsson’s research is that deliberate practice takes many hours (as much as 10,0003) of repetitive, iterative and difficult training. To many people, this will sound a lot like hard work.

Through this lens, it would seem that hard work and talent are not only linked, but in fact hard work is a pre-requisite for talent.

"To experts, what looks like work from the outside, is play from the inside."

The above statement feels incomplete. Anything, done to the extreme that it qualifies to be an expert, feels like it must also imply some hard work.

To use a sporting example, let’s take Cristiano Ronaldo as an expert footballer. Whilst he loves football and surely considers much of it play, it seems unreasonable to me to suggest it doesn’t also involve hard work. Long hours in the gym. Many hours of travel. It’s not all play.

In an office based context, let’s use the example of a programming expert. Whilst the creation of code may be considered play, there are many other facets which are likely less so. Consider problems with the hardware or writing of documentation.

In any job, no matter how much you enjoy it, it would seem incomplete to think that there isn’t at least some part that is less fun. That less fun part is the hard work. Therefore, it follows that hard work and talent feel more connected than in Naval’s statement above.

Comparative Play

However, it does seem like good advice to try find an area of work which you enjoy more than others. This way, by virtue of comparative play, you have a comparative advantage.

Some people may idealize this as “finding your passion” but I think Naval says it more concretely below:

"So an area to focus on - find something that feels like play to you but others think is work"

This is great advice. If you have some natural tendency that allows you to find joy in something that people a) value and b) find hard, double down on it.

Hard Work and Luck

I also wanted to make the connection between hard work and luck, which is missing from Naval’s podcast.

In Marc Andreessen’s essay, Luck and The Entrepreneur, he discusses four types of luck. The most relevant for this discussion is luck II, which loosely transcribed is the luck we attract through being active, doing stuff and working hard. Or to take a quote from the book Marc references:

"I have never heard of anyone stumbling on something sitting down"

The implication here is that hard work makes us lucky.

Naval himself has referenced the above in his own post, Making Money Isn’t About Luck, where he writes:

"Then there’s luck that kind of comes through persistence, hard work, hustle, motion, which is when you’re just running around creating lots of opportunities."

Takeaways

When your choices have higher leverage, judgment is increasingly important.

Hard work and good judgement are not mutually exclusive. Don’t make this false choice.

The perception of hard work can be important in of itself. Qualify if that is true in your environment.

Hard work and talent are often linked via deliberate practice. If you consider your profession a craft, you’ll likely benefit from deliberate practice.

Be aware of those skills which you find easy, but others find hard. If it is also valued by society, it is the basis of a good career.

Hard work can make us more lucky.

Given the above, I still value hard work.

[Update - 21 May 2020] - p.s. So does Naval.

[Update - 8 July 2020] - I collected some other ideas from Naval.